Very few people will know exactly what the UK’s unwritten constitution actually consists of – or that it keeps evolving as those in power push its limits. Nobody has mastered this like Britain’s current Prime Minister.

Although Thomas Paine wrote the Rights of Man in 1791, the English upper-classes were determined never to have a constitution built on citizen’s rights, like revolutionary France and America – where written constitutions aim to protect citizens from the machinations of the corrupt, rather than protect the elite. Ever since Magna Carter, Britain has been ruled by an increasing complex patchwork of conventions aimed at keeping the establishment in power.

The sovereignty of Parliament – which the Vote Leave campaign, led by Johnson, told us was what Brexit was seeking to restore – is the only solid part of the UK’s unwritten constitution, but it is effectively built on sand.

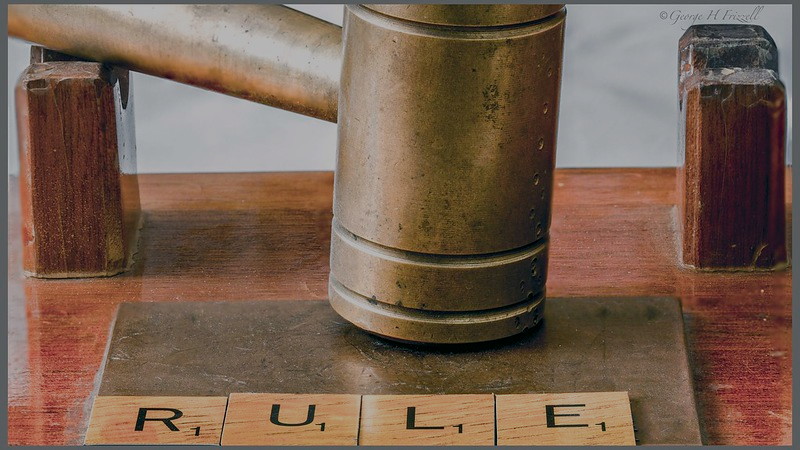

Nowhere is more riddled with conventions than Parliament, with much of its arcane procedure driven by them. Importantly, they are meant to constrain the behaviour and ethics of governments. But Boris Johnson’s Government is flouting these norms like never before – and there is little to stop it.

All we are left with are a few unrelated parts of constitutional law such as the Parliament Acts, which limit the powers of the House of Lords. And, as the unlawful prorogation of Parliament in 2019 showed, the very functioning of it is vulnerable.

The most important convention governing the behaviour of all public servants has been found in recent years in the seven Nolan Principles, named after the first chair of the Public Standards Committee set up in 1994 to advise the Prime Minister. The current Government appears to have broken or pushed all of these to the point of no return.

We seem to have arrived at ‘post-Nolan’ British politics – breaking the pact between our representatives in Parliament and the electorate that the truth will be told.

Some examples

The case of Priti Patel is perhaps the most obvious example:

“The bullying allegations made against the Home Secretary were investigated by the Cabinet Office but the outcome of that investigation has not been published, though completed some months ago,” observed the current chair of the committee, Lord Weardale. “There may be legal complexities underlying this but those have not been made clear and this does not build confidence in the accountability of Government.”

As one of the most senior public servants, Patel should follow the Ministerial Code. However, although the Prime Minister has an advisor on minister’s interests, he can only advise and Boris Johnson himself has the ultimate power in such situations. He exonerated Patel of the bullying claims against her and sacked his advisor.

Whilst ministers being appointed from those who sit in the House of Lords is an established convention, it has been stretched by Johnson, who used it to flagrantly to retain ministers he lost in the 2019 General Election, such as Nicky Morgan and Zac Goldsmith. Indeed, David Frost, a bureaucrat who has never been elected, led the final stages of the Brexit negotiations.

If Johnson’s Government has killed convention, is the rule of law and the judicial system the saviour of Britain’s political system?

Unfortunately, probably not. This Government has an 80-seat majority in the Commons so it can easily pass the laws it wants – including weakening the right of citizens to bring judicial reviews of its decisions,, which has been used to great effect during the pandemic by the Good Law Project and others.

This Government’s success at breaking conventions might have hastened its downfall. For hundreds of years, the establishment was careful to keep conventions within acceptable limits while its elite members used them to maintain and strengthen their position. Now, those conventions appear to have been destroyed. Where this leaves Britain’s ruling elite and our democracy in the future remains to be seen.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to react!